27

Apr

2018

Player Pianos and the Origins of Compulsory Licensing – Some Details of its Origins

The Music Modernization Act just passed the House as I’m writing this, and it seemed apropos to look at the origins of mechanical licensing in the 1909 Copyright Act. The story has been told before (although not in a dedicated article or book), but I’ve found a number of aspects of the story that I believe have been largely forgotten, along with a few documents that I’ve scanned which are pretty cool to see. Accordingly I’ve compressed parts of the narrative and expanded the parts where I have something new to add. One of these days I’d like to write a book on the 1909 Act, or at least put this stuff into an article

Music is no longer written on piano rolls and our laws shouldn’t be based on that technology any longer either. The #MusicModernizationAct brings our music laws into the 21st Century digital era.

— Bob Goodlatte (@RepGoodlatte) April 11, 2018

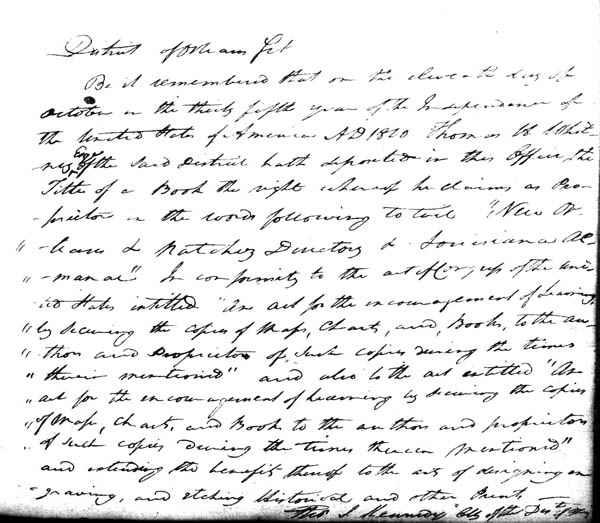

The first sound recordings that could be played back were made in the 1870s, and the technology was commercialized effectively beginning in the 1890s. In these early days the legal aspects of the various early sound reproduction systems were generally lumped in with another technology that developed at around the same time, the player piano,1 and in 1888 Harry Kennedy brought suit in the U.S. Circuit Court in Massachusetts, arguing that the inventor John McTammany had prepared Kennedy’s song Cradle’s Empty, Baby’s Gone, copyrighted in 1880, on a piano roll for use in a player piano (the song is a serious downer, fair warning). The casefile from the National Archives (which I originally shared last year) shows that in 1882 the Automatic Music Paper Company paid Kennedy a license fee, and published an authorized piano roll indicating that the song was used with permission. In fact, although the reported decision does not make it clear, the Automatic Music Paper Company was Kennedy’s co-plaintiff in the case.2 However, in a brief decision the Court held that programming a paper reel with punches for use in a player piano did not infringe the copyright of the musical composition which was played back from that paper reel. The matter was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, but in 1892 the Supreme Court dismissed the case without an opinion. 145 U.S. 643 (OT 1891 No. 168)

It would be another decade before another reported decision on mechanical reproduction, but at the beginning of the twentieth century one George Rosey was accused of selling sound recordings of two songs on wax cylinders – “Take Back Your Gold” and “Whisper Your Mother’s Name.” I’ve scanned the appellate case file of the DC Court of Appeals, and the briefs show the conflicting positions taken by the parties to the case, where Rosey based his argument on prior caselaw – the 1888 Kennedy decision and the then-recent English case of Boosey v.Whight, 1 Ch. 836 (1899) and 1 Ch. 122 (1900). By contrast the music publishers of Joseph W. Stern and Edward B. Marks looked to broad principles of copyright to assert that recording a copyrighted song constituted infringement. In 1901 the DC Court of Appeals (now the DC Circuit Court of Appeals) held similarly regarding sound recordings, finding that a sound recording did not infringe the copyright in a musical composition.

As I mentioned (I’m not sure others have noticed this), as early as 1882 the Automatic Music Paper Company was paying royalties to songwriters for mechanical reproduction, in spite of the lack of clear legal precedent saying they had to. Later in that decade the Automatic Music Paper Company merged with the Mechanical Orguinette Company, and the resultant company would be named the Aeolian Company. Aeolian would continue its predecessors practice of compensating songwriters for use of their songs. Its motivation for starting this practice is unknown (at least to me – feel free to educate me in the comments) – was it alruism and a sense of duty, did they believe they had a legal obligation, or, as critics increasingly charged, did they intend to establish such a right once they already held licenses to most popular music, setting themselves up to dominate the player piano market using copyright?

When the White-Smith Music Publishing Company sued the Apollo Company to assert that Apollo had sold piano rolls that infringed their copyright in the musical compositions, it was generally understood that Aeolian was actually behind the litigation.3 The case slowly worked its way through the Courts, and while this was happening, in 1905, the gears began turning on a major revision to the copyright laws. In June of 1906 Congress held hearings, and the transcript shows that Aeolian’s opponents showed up in force to argue that Aeolian was trying to create a monopoly in the player piano using its licenses to musical compositions. Aeolian was not represented at these hearings, but at their behest a young Nathan Burkan published a pamphlet with the unwieldy title of The Charge That The Passage Of The Copyright Bill, Senate Bill 6330, Will Create A Monopoly In The Manufacture Of Automatic Musical Devices Is False. The pamphlet on the one hand acknowledged that Aeolian had, in 1902, made contracts with many of the major music publishers for mechanical rights, assuming a court found such rights existed. Aeolian also agreed to fund the litigation, and according to Burkan they had already expended $50,000 in legal fees, the equivalent of over $1.2 million today. However, they argued that Aeolian had not secured contracts for all popular music, and further that such contracts explicitly did not include rights for sound recordings, which were likewise ascendant. Nonetheless, the response does leave a certain lingering impression that Aeolian acknowledged that they would have at least a dominant position in the player piano market if a law giving the owners of copyrights in musical compositions an exclusive right of mechanical reproduction.

After the case arrived before the Supreme Court, but before argument, the defendants moved to dismiss the case, arguing that the amount in controversy was not significant enough for the Court to have jurisdiction. This motion is found at the end of the case file held by the National Archives, and has not to my knowledge been previously discussed. It’s not clear why Apollo would move to dismiss at this point if the amount in controversy was so minor anyway – they’d come so far, one would think they would want to be vindicated. One possibility is that, if the case was a test case with a willing defendant, Aeolian grew concerned that the winds of the case were blowing against them, and tried to get out before the Supreme Court issued a decision.

Sure enough, in 1908 the Supreme Court affirmed the earlier decisions regarding mechanical reproduction in White-Smith v. Apollo, and held that the 1870 copyright law did not recognize mechanical reproductions as “copies.” However, the Court made clear that Congress could step in and remedy this inequity, and in response the 1909 Copyright Act provided compulsory licensing provisions for “mechanical” reproductions of copyrighted musical compositions, including sound recordings. It was widely understood that the compulsory nature of the licensing was meant to prevent another entity like Aeolian from dominating the market using exclusive licenses.

Roughly ten years later, the Federal Trade Comission investigated Aeolian for various antitrust claims, including price-fixing, leading to a cease and desist order (at pg. 124). However, Aeolian survived far longer, and long after player pianos had left the mainstream, going through a series of mergers and finally declaring bankruptcy in 1985

- There were actually different technologies and names for mechanical organs at the time, but the details are only incidentally relevant and I’ve chosen to simply describe everything as player pianos and piano rolls. ↩

- The casefile is pretty interesting in general, and the answer filed by the defendant includes a detailed description of how the player piano worked. ↩

- The rolls were actually made by QRS, which is still in business today as the last maker of piano rolls. This section is going to be compressed a bit, but you can read a longer version of the story of White-Smith v. Apollo at pp. 31-33 of my article Common-Law Copyright. ↩